My American Dream

Written by Chidi Akusobi

Edited by Chidi Akusobi & John Stevenson

[I kept the stage directions to retain the speech feel. The visuals I used for the speech labeled in the text as "Slide #" are at the end of the post]

Good afternoon everyone. My name is Chidi Akusobi and I’m a Class of 2008 graduate of Horace Mann.

[POINT to a place on stage] Not so long ago I took Acting Seminar on this stage with Woody Howard.

[POINT] And I sat up there on the balcony with my group of friends belting out the alma mater.

One of my best friends from HM is here today, Sunanda Nath! Where are you? Thank you for coming.

My friends and I were all tone deaf, but we sang with confidence. It’s the Horace Mann way!

Before I begin, can we give a round of applause to Ms. Bartels for organizing an amazing Book Day. Also, I want to thank Dr. Casdin, my junior AND senior year English teacher, who taught me how to critically engage with text. I hope I make you proud today.

Now, when I graduated, I thought I would be forever done with homework assignments from Horace Mann. I was wrong.

This latest assignment though brought me back eagerly.

Between the World and Me came to me at a time I needed it the most. The book made a profound impact on me by forcing me to reconcile my feelings on: Race and racism in this country. My black body. And the American Dream. [address audience x3]

On June 17, 2015, a 21-year-old white man entered a church in Charleston, South Carolina and killed 9 black men and women. [SLIDE 2] Their ages ranged from 26 to 87. They were gathered in peace and fellowship at one of the oldest black churches in the nation.

They welcomed this man into their Bible study with open arms and opening his arms, he buried them. (pause)

I woke up that morning and began my usual routine. Like the good millennial I am, I checked Facebook and was immediately bombarded with a deluge of posts, messages, and news articles. The headlines were everywhere.

Soon after came the public grieving of yet another black body lost to racialized brutality. This time the body count was nine.

That summer I was researching with Pardis Sabeti, a high profile scientist at Harvard Medical School who spearheaded the sequencing of the Ebola virus during the 2014 outbreak. I wanted to do my PhD in her lab, so I was working long hours.

That morning, when I learned about the shooting, I told myself that I had to deal with this news later. Like so many black people do, I put the news in a box -- barricaded that box -- stored that box in a closet…and walked away.

I then focused - on the task - at hand. Getting to lab. Which started with closing Facebook and going through the morning motions.

Just as I was putting on my coat, ready to leave, I began to weep uncontrollably.

And endless stream of grief; an ocean of sorrow, with waves battering my mental barriers, threatening to smash open that barricaded, stowed away box.

I did make it to lab that day. Mostly all there.

One month later, on July 13, 2015 [SLIDE 3] the world learned that Sandra Bland died in police custody after a routine traffic stop. Her death was ruled a suicide.

One day later, Between the World and Me was published.

James Baldwin, the spiritual grandfather of this book, famously said “to be black and conscious in America is to be in a constant state of rage.”

With rage, though, there was also grief.

That summer I felt vulnerable and bruised, a rugged patchwork of scrapes from too many nasty falls. Between the World and Me came at a time when I felt like my black body was dispensable. That my life. Mattered. less.

I had turn to this book for solace. [Hold the book high]

[SLIDE 4] In retrospect, just like shopping on Amazon, I should have looked at the reviews first.

But I dove in and was left with emotions. Lots of them.

I’m curious, how many people after reading this book felt angry, upset, defeated, or all of the above? Good. Know that you’re not alone.

After reading Between the World and Me I was also left with a central burning question. One that Coates asks himself.

He writes to his son: [SLIDE 5]

“I tell you now that the question of how one should live within a black body, within a country lost in the Dream, is the question of my life”

But what does an American Dream that “rests on the backs of blacks” mean to a Nigerian family lured here by this Dream, a dream that is a stormy mix of fantasy, reality, and nightmare?

Notice that I said “an” American Dream, not “my” American Dream.

Because in some ways, my American dream isn’t really mine. Or at least, it did not begin that way.

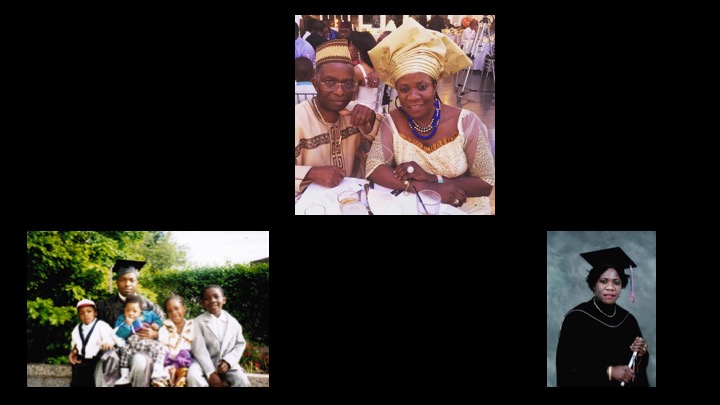

[SLIDE 6] It started with my parents who are here to today. Can you raise your hands? Kedu! That’s Igbo for hello.

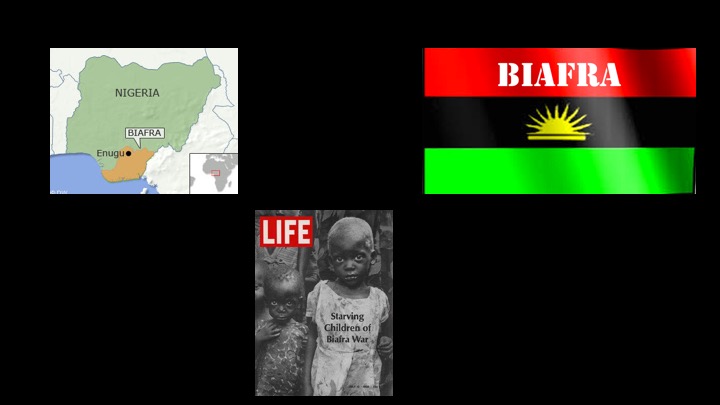

My parents were born shortly after Nigeria won its independence from the United Kingdom in 1960.

And from 1967 to 1970, the Nigerian Civil War was fought for the future of Biafra, the country that Igbo people, my ethnic group, attempted to create for ourselves.

Three years left millions dead, mostly from starvation. My parents lost family, friends, and kinsmen to this war. This trauma casts a shadow over them and the region that still lingers today. Lingering trauma gave rise to big dreams. And this big dream is captured by the poem etched onto our Statue of Liberty: [SLIDE 7]

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free

The wretched re-fuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me”

My father believed his dream of becoming a physician was not possible in Nigeria, but it could be possible for his children in America.

On May 25th, 1990, my father arrived in New York City, and two years later my mother and I excitedly joined him.

[SLIDE 8] Everyday my parents worked hard for the money. Day and night they toiled. Fitting in time to study to become nurses, while providing for 4 children, and taking care of large families they left behind in Nigeria.

They sacrificed so much. To my mother and father, I want to thank you here in front of everyone for all that you’ve done.

This includes passing on the Dream to me.

But place shaped me too. My parents had Biafra. I had our zip code, 10455. [SLIDE 9]

Anyone here from the Bronx or the South Bronx? Aye! We out here!

Let me tell you about the greatest Netflix show not yet released. It’s called 10455.

Set in the backdrop of failing schools, high crime rates, and poor infrastructure, I imagine Buzzfeed writing an article on “the 27 times 10455 was the gritty antidote to Beverly Hills 91210”

(By the way Buzzfeed is always telling you 45 things you never thought you needed to know, but now do)

In all seriousness, the South Bronx and West Baltimore, which Coates describes with beautiful clarity are examples of neighborhoods intentionally created by years of racist policy.

They are also neighborhoods where the American Dream seems impenetrable.

Some zipcodes are paradise. And some zipcodes are nightmares.

But the American Dream is also an aspirational fantasy: They say - if you play by the rules, hard work will pay off. Honestly. Truly.

But what happens if you live in a place where hard work and the pay off are not in a 1 to 1 ratio?

And what if in your school opportunities are scant and positives role models are rare?

What do you do when your neighborhood clips your wings before you learn to fly?

PAUSE.

To quote the foremost philosopher of our generation “started from the bottom now we’re here.” I reflect on this lyric whenever people ask me where I’m from. Now - my answer usually depends on their tone of voice and why I believe they’re asking.

So naturally my response varies from the Bronx, to Nigeria, or I’m a global citizen thank you. [passive aggressive voice]

Most of the time I say from the Bronx, and let me tell you, people’s responses can be wild.

Sometimes people respond with exaggerated sympathy, “aww, you’re from the Bronx?!?! That’s so amazing”

And other times astonishment. “Wow. You’re from the Bronx….I guess I can kinda see it now.”

One person at the University of Cambridge actually asked me how I made it out alive. I replied “by dodging bullets like a ninja.” [DODGE]

But zipcodes are not walls.

And sometimes other people dream the dream for you until you’re mature enough - to dream for yourself.

Along with my parents, Prep for Prep dreamed for me too.

[SLIDE 10]

But they didn’t stop there. Prep provided me with real opportunities. Role models who looked liked me. And most importantly the confidence to believe in myself and my potential.

In short, Prep gave me wings. And provided me with my first real window to the American Dream.

Are there any Prep students in the audience? Yes! It makes me so happy see you all! Prep 4 Lyfe!

For those of you who don’t know, Prep prepares gifted students from inner-city public schools to attend NYC’s best private schools.

I still remember my Prep admissions visit to Horace Mann. I sat in on a 6th grade science classroom, on a day when students were performing an experiment on erosion!

[slowly] A science class was doing a science experiment! The reason why I was so shocked is because I came from MS 135, where we had science class once a week and by mid-year had done exactly….one and a half experiments.

That day I told my parents that I had to go to Horace Mann. It was either Horace Mann or that place that shall not be named.

Riverdale. [Whisper]

[SLIDE 11] On September 2004, I started 7th grade at Horace Mann.My first year at Horace Mann was a period of great transition.

First of all, I started off by going to new kid Dorr Orientation and everyday I asked myself - why am I in the woods?! I certainly did not leave MS 135 for this.

The biggest transition for me though was demographic. Those of you from Prep may be familiar with this. I went from attending a public school with predominantly black and Latino students, to being one of four black boys in my grade.

I felt for a long time a gnawing sense of discomfort. Did I belong here? Was there a seat at the table for me?

After school, I boarded the storied Bronx Bus, and saw my classmates board buses that took them down Park Ave and Broadway, glitzy streets that until then were as fantastical to me as dinosaurs.

What compounded my initial discomfort was the fact that I was a straight B student. And let me tell you, my Nigerian parents were not happy.

One particular memory stands out to me because it’s in fact the very day when my parents’ American dream finally crystalized in my mind.

On the final day of 8th grade, I came home, report card in hand, excited to show my parents.

This time, I had gotten 3 B+’s. THREE! This was huge folks! Life was good! And I was sure they’d let me see a movie or better yet finally let me go to a friend’s place for a sleepover. That’s all I ever wanted.

I walk up to my father and proudly show him my report card. He looked at it and did something all Nigerian children fear.

Pause.

He took a moment of silence. Now in these parental moments of silence you don’t know what is coming, how it’s coming, or even where it’s coming from. What you do know is that something is coming. And it ain’t good.

So I’m standing there - casually waiting on infinity, when my dad finally breaks his silence. He says:

“Chidiebere come sit down, sit down.” So I sit.

My mother suddenly appears out of no where -- I swear sensing teachable moments is her special power -- and together, like coordinated Williams sisters, they proceed to give me a spirited, and I do mean spirited, lecture-sermon. The kind Nigerian parents are too good at giving.

They discussed the sacrifices they made leaving Nigeria to start afresh in America as strangers - in a strange land. They reminded me how lucky I was to study at Horace Mann, where opportunities fell from trees outside Tillinghast Hall.

To my parents - education was the major key to building a better life for ourselves in America. And my 14-year-old self was squandering it away with mediocrity and desires to sleep over with friends.

Their lecture-sermon ended with the old adage spoken by generations of black parents, this time with a Nigerian twist. [SLIDE 12]

[ACCENT] “Ah ah. In this Ah-me-ri-ca, you have to work double double [HANDS]. Or you will be finished”

It was on that day, I took ownership of my parents’ American dream. And made it my own.

So what did I do next?

Like a Pokemon or Digimon for those of you in the know, I evolved into my new form: [SLIDE 13] Beast Mode.

From 9th grade - to my graduation from Yale in 2012 - to the University of Cambridge, I channeled Rihanna’s “Work” and Beyoncé’s “Formation”. I dreamed it. I worked hard. I ground till I owned it. Slay was not a mainstream concept at the time, but that was certainly my aesthetic.

In my mind - the more I excelled in academia, the closer I would be to the American Dream, which to my parents meant becoming a doctor, lawyer, AND engineer. All by 35. LITERALLY.

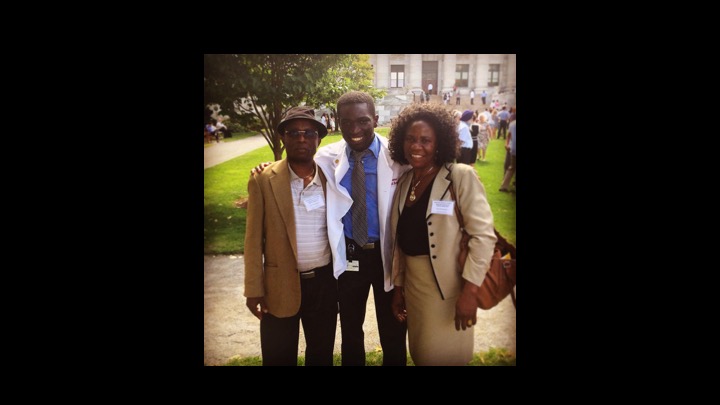

[SLIDE 14] On March 4th, 2014, I was accepted to the MD-PhD program at Harvard Medical School. Finally! I thought, all this hard work had paid off.

You can imagine, the joy on my parents’ face when they attended my White Coat Ceremony. To them, my white coat symbolized the culmination of years and years of sacrifice. My white coat was the physical embodiment of our American dream.

[solemn] And yet, zipcodes lingered like the shadow of a civil war.

In Social Medicine, I learned of rampant disparities in healthcare that disproportionately affect minority patients. I learned about social determinants of health and how poor neighborhoods lead to sick people.

I was shocked to learn how my chosen profession systematically fails black, Latino, and Native American patients.

[SLIDE 15] During orientation of first semester, the Ferguson protests began.

The images of militarized police in Ferguson, Missouri were horrifying, haunting even. I did not recognize the America I grew up in. And people across the nation asked ourselves, are we dreaming?

[solemn] Some zipcodes are paradises. And some zipcodes turn into warzones.

Furthermore, nobody was held responsible for the tragedies of the summer of 2014. There were three back-to-back non-indictments for the police offers involved in Eric Garner. Michael Brown. And Tamir Rice’s deaths. Three.

This lead me to question why, much in the way Coates does, is achieving the Dream a noble goal? Especially if in the end black bodies could be extinguished by an agent of the state or by disparities in medicine?

Lingering trauma gave rise to big dreams. And this big dream found a hashtag and a movement: [SLIDE 16] BlackLivesMatter.

It began as a whisper. BlackLivesMatter. A promise. BlackLivesMatter.

The lightest of breezes dancing on an ocean of sorrow filled - with the funeral cries of 10,000 families.

That breeze. That promise. Became a wind -that blew across America carrying a message told again and again of our Lady Freedom: [SLIDE 17]

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.”

A wind of sacrifice. A wind of freedom. A wind of justice.

[Audience x3]

A wind….with the fierce urgency of now. [center]

I learned from Dr. Palfrey’s physics class that objects do not move or bend unless a force is applied to them.

So what is the force that bends the moral arc of the universe towards justice?

It’s Us. You and me. [GESTURE] It’s anyone who stands up for what’s right and demands change. [SLIDE 18]

That semester in medical school, I helped found the #WhiteCoat4BlackLives chapter at Harvard Medical School where we worked to combat institutional racism in medicine.

On Dec 10th 2014, medical students from seventy schools around the nation staged die-ins to denounce racial injustice.

[slow down] We used the privilege afforded to us by our white coats to highlight the struggle of racism in medicine, and society at large. After all, racism is a social disease.

And this is the last point I will leave you all with. The concepts of privilege and struggle. To me, they are two sides of the same coin.

I have been privileged to have the parents I did, attend the schools I’ve attended and be supported by excellent role models and amazing friends.

Yet there are many times when I struggle with what it means to live in this country with a Black. Body.

[solemn] Honestly, sometimes, it feels like all of the universe is between the world and me. And sometimes, this feeling makes you cry. [SILENCE]

But what comes out of the winds of sacrifice, and the winds of freedom, and the winds of justice blowing over an ocean of trauma is hope.

For the lone and helpless wanderers - in the dark and stormy sea, hope is the beacon that lights the way to life and liberty.

Hope. Famously echoed by President Barack Obama. HOPE he says [SLIDE 19]

“is that thing inside us that insists, despite all evidence to the contrary, that something better awaits us if we have the courage to reach for it, and to work for it, and to fight for it.”

In reality, the American Dream has always been a project. A project whose work never ends, but whose promise [pause] is fueled by the audacity of hope.

I’ll close with my favorite line from our alma mater. Don’t worry, I won’t sing it.

For knowledge is the truth that makes us free.

PAUSE.

Cherish this book [HOLD BOOK UP]. Cherish Book Day. Cherish knowledge. And then go out - and help make the world - more free.

PAUSE.

[SLIDE 20] Thank you.