Introduction

On Christmas Day 2011, I arrived at my mother’s childhood “compound.” Nigerians describe their homes as compounds, a word imbued with emotional gravity, symbolizing not only the physical home, but also the surrounding area. Calling the place you live “compound” invokes a feeling of ancestral bond to the land, a connection to your roots.

A trip to my mom's compound in Etiti, Imo State, 5 days before my 1st birthday. The side eye with a smile is my mom's forte. To the left is my mom's older sister, Aunty Chi.

My mother’s compound is located in Etiti, a village in Imo State known for its elaborate ‘coming of age’ initiation ceremonies and masquerades. The compound contains two houses, an outdoor kitchen, and a shed where my grandfather stores his prized but now rusty machine that turns palm nuts into the national delicacy, palm oil. My grandfather used this machine to support his family of over 16 children during times of prosperity and times of strife like the Nigerian Civil War. To the left of the shed is an animal pen where my uncles tend to the family’s goats and chickens. A gate, dutifully manned by my youngest uncle, Okechuwku, encloses the entire compound.

My siblings and I arrived at the compound with our luggage and strong American accents. We had barely stepped out of the car, and already a swarm of aunts and uncles surrounded us. There was an eruption of emotion with screams, cries, shouts of kele Chineke “thank God.” Hands were jubilantly thrown in the air, on the ground, in the air and on the ground simultaneously (Never underestimate the capacity for Nigerians to dramatize - anyone who’s seen a Nollywood movie knows what’s up). And on everyone’s face were smiles: wide, beaming, filled with joy.

Finally! The American and Nigerian sides of the family were reunited after nearly a decade of communicating by phone on birthdays and holidays. Children of a diaspora know how these short, loud conversations with far-away relatives go.

“How fa? How is school? We thank God. How is your [insert name of sibling]? How is your [insert name of other sibling]? *phone breaks a little* We are proud of you o. Okay, give the phone back to Mommy.”

On Christmas Day in 2011, the distance was finally closed and prayers were being delivered in person. And the years of being apart from each other infused the welcoming with epic levels of love.

At some moment during this exchange, tears gently filled up my eyes.

Shout out to me (hehe) for wishing my biffle a Happy Birthday thousands of miles away. Real Friends

At last! I had returned to my Kansas aka Etiti, my maternal home, where my aunts and uncles greeted me with arms so wide they could hug the Earth. From then on, it didn’t matter where life took me - The Bronx, New Haven, London, Boston, Wakanda, or Mars. No distance could sever my ties to the place where the tapestry of my family was woven.

This memory of Christmas Day came to me after watching Black Panther. And the question I asked myself was, “Why?”

To answer this question, I did something we as a society no longer reward in today’s media environment. I didn't immediately write a review titled “22 Times I Screamed YASSSSSS King at the Screen while Watching Black Panther” (though I could have). Instead, I stopped to reflect on what we could learn from the film, and why the memory of tearing up at my maternal home came roaring back to me.

Since Black Panther’s release, there has been a deluge of think pieces analyzing every aspect of the movie. And for good reason. Watching Black Panther was like drinking cold water from a Scandinavian spring after a trek across the Sahara. We as a culture were thirsty for this movie. Thankfully, it delivered and slayed the box office. Hopefully, now the Hollywood misconception that predominantly black casts aren’t profitable will be buried wherever KellyAnne Conway buried her soul.

I love Black Panther for many reasons. From the storyline to the acting, the cinematography to the costume design, Blackness in all its glory emanated from the movie screen and lit our parched hearts. I lived, only to die, and be reborn - in Jabari land with my tribe.

In case you're wondering, M’baku is a Nigerian man full stop. His accent, mannerisms, dramatic haughtiness, all are made and distributed in Nigeria.

My face next time someone talks to me about #AllLivesMatter. "ARE YOU DONE?" "I WILL NOT HAVE IT O." *feeds to children* 😜

Source: Comicbook.com

Between characters barking at a white man to be quiet (the shade of it all) and snatching their own wigs to use as a weapon (gif of the year?), Black Panther addressed a myriad of themes, cultural touchstones, and third rails that have been thoroughly discussed in the think piece tsunami that followed the movie.

For convenience and for the culture, fellow SLR contributor, John Stevenson and I compiled and categorized a collection of Black Panther think pieces. You’re welcome: link.

After reading these think pieces and seeing the movie a second time, the connection between Black Panther and tearing up at my maternal home began to crystallize. From this vibranium crystal emerged the central themes of home and homeland. It is through this lens that I began to understand the beauty, genius, and tragedy that powers Black Panther.

Part 1: Wakanda, a beautiful homeland

The director, Ryan Coogler, did a marvelous job of not only bringing Wakanda to life, but also instilling a sense of Wakandan identity and pride in each of the characters. This includes T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman), who with grace and killer regal outfits accepts the role of Black Panther to protect the Wakandan way of life. It also includes Okoye (Danai Gurira), who resolutely proclaims she would kill bae for Wakanda “without question.” This was the hardest line in the movie, and poor W’Kabi (Daniel Kaluuya), fresh off the trauma he experienced with problematic white-woman bae in Get Out, stood down with the quickness.

Chris: Will you allow me to be lobotomized in the name of white supremacy? Rose: Without question.

Source: The Coli

Throughout Black Panther, we saw characters fight for Wakanda, by upholding its traditions and pressuring Wakanda to adapt to a changing, more connected world. Nakia and Okoye’s beautifully-acted confrontation after Killmonger becomes king illustrates this point. What made that scene so powerful is that while they differed on how best to serve their country, their mutual love for Wakanda was palpable and undeniable.

I'm requesting my graduation party be held on a waterfall. Wakanda inspired outfits and chest choreography required.

Source: Giphy

And the waterfall scene? Sorry TLC. From now on, I'm chasing waterfalls, bouncing my chest, singing ‘T’Challa ooo, T’Challa o.” This scene was gorgeous from start to finish. I was transported to Wakanda and was out here rooting for the King even though I met the man 15 minutes ago.

Wakanda as a homeland is revolutionary. So often, popular imagery African countries showcase destruction and pillaging through the slave trade, colonialism, or civil strife. “African Booty scratcher” is a term many African immigrant children, including myself, are called growing up. In turn, some of us are pushed to hide our heritage due to embarrassment and fear of ridicule.

Black Panther bucks all of that. The movie counters the popular imagination of Africa as the “shithole” continent, while proudly asserting that the choice between tradition and modernity is a false one peddled by the West. With the introduction of Wakanda in our popular culture, a seed of new found respect for the continent has been planted. I go to sleep happy knowing that positive images of the continent, which birthed mankind is transmitting all around the world.

Part 2: Wakanda as spiritual home to black people

After the release of Black Panther, black people around the world embraced Wakanda as a spiritual home. We saw this in the memes people posted of traveling to Wakanda and pictures of people around the globe making the ‘WakandaForever’ sign 🙅🏿♂️.

Wakanda is a pan-Africanist dream come true. It’s a location the African Diaspora can claim connection to, and through that connection, uplift themselves and their communities.

But how does fictional Wakanda accomplish all this?

My Black Panther outfit inspired by the Pan-African movement. Goal: serve visiting scholar from Wakanda realness.

Lupita Nyong'o, my forever inspiration. I put my Black Panther premiere outfit alongside hers to give the illusion we're on the same level.

In Wakanda, we get an Afro-futurist playground. We see black characters who love their country and fight for it. We see a dark-skinned woman in Bantu knots as the love interest of the king. Tribes are out here proudly embracing their cultural traditions and all of this is occurring in the absence of the white gaze. Wakanda represents that rare place where one’s blackness isn’t questioned or considered a threat.

Wakanda is in short our safe space. And an inclusive one at that. I credit Ryan Coogler for centering female characters who drove the plot and were the chief protectors of Wakanda. Black Panther also played on several touchstones from African and African American cultures.

T’Challa wearing those old sandals was a nod to all the African dads and uncles who swear by those open toed sandals. I’ve been trying to get my dad to retire his pair for nearly two decades.

I don’t know what African dads love more: these sandals or asking their children to pass them the remote.

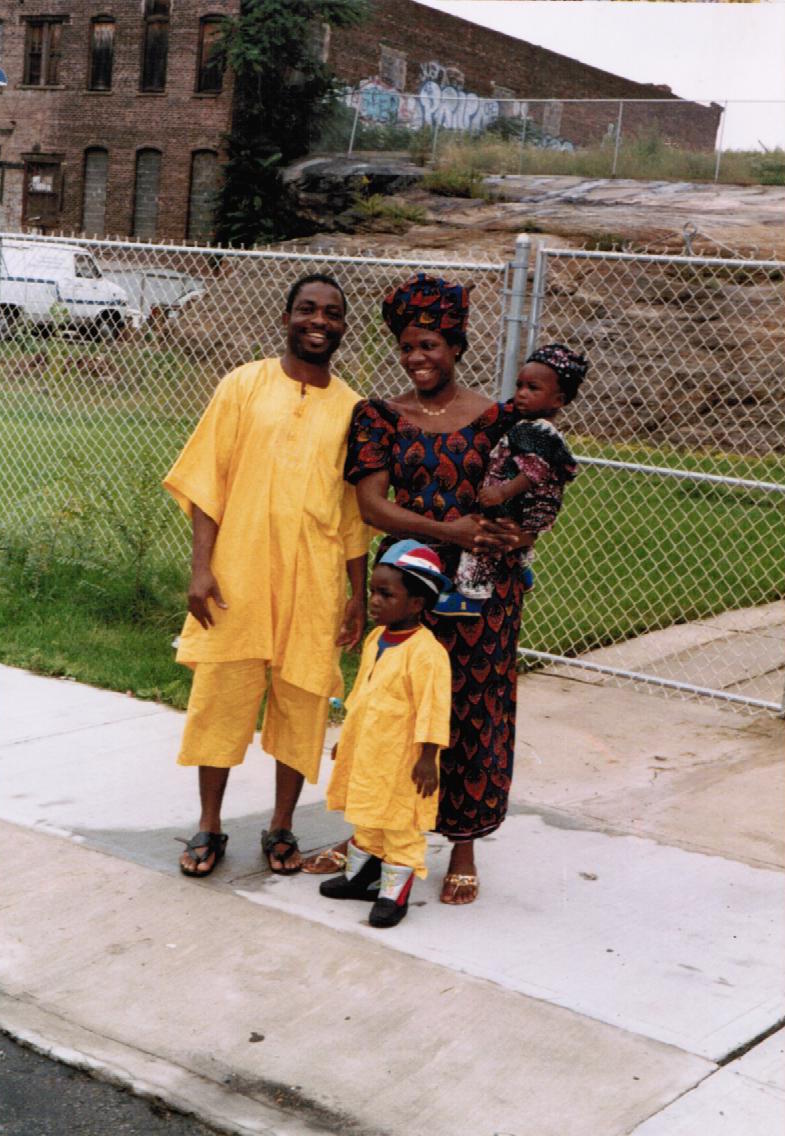

Picture of my parents, sister, and I during our early years in the South Bronx. My dad is proudly rocking the open-toe African dad sandals straight from Nigeria.

Interestingly, after Black Panther’s release, people all over the world claimed citizenship to Wakanda. Why? Because although fictional, mini-Wakandas have always existed in the souls of black folk. Wakanda’s concealment is an apt allegory for the ways minorities create and escond their safe spaces – lest they be infiltrated, destroyed, or appropriated by the majority.

Places like the black church, black Greek parties, and cookouts are refuges where black folk can just be. No magic needed, just care free. Similarly, world-changing art forms like jazz and hip-hop grew out of black self-expression in the repressive ante-bellum and Jim-Crow South (in the case of Jazz) and urban blight and poverty thrust on black and brown communities in the Bronx (in the case of hip-hop).

The South Bronx is next gentrification frontier. Here's a rendering of luxury apartment buildings planned by HillWest architects.

Jazz, hip-hop, and other traditionally “black” sounds have since been adopted by white artists who regularly go on to earn more money, fame, and critical acclaim than the original black creators. And when we examine the history of autonomous black spaces like Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma, these refuges often end in destruction by violent members of the white majority, or in gentrification as seen in cases like Harlem, NY. With these histories in mind, Wakanda’s decision to hide as a means of protection, lest it be attacked or exploited, makes total sense.

This is why Shuri yelling “Don’t scare me like that, colonizer!” to Agent Ross was not only a great laugh line, but also a poignant social critique (Black Panther was full of them, 👀 British Museum). Another broken white man was walking around her lab looking a little too eagerly, a little too “let me steal this technology and take it back to my home country”-y. Agent Ross’ presence disrupted the safe space that is Wakanda and colonization had become a very real threat. That’s why Nakia telling Okoye that she “locked Agent Ross up, so he won’t do anything” isn’t just a throw away line. He, by virtue of being an opportunistic white man in an all black space was a credible danger. Wakandans knew it, the audience knew it, the world experienced it.

Now that Wakanda revealed itself to the UN (low key should have been the African Union), the stage is set for a sequel. I’m hoping Wakanda looks at the histories of their neighboring countries and learns something. Because we’re all rooting for Wakanda and, by extension, the protection of our sacred safe spaces.

My reaction if Wakanda is exploited, invaded, or colonized in the sequel

Part 3: Who is lost? You or your homeland?

“The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth”

The principal villain of the movie, Erik aka Killmonger, is the sole black character without a strong connection to Wakanda. This isolation, caused by T’Chaka’s fratricide of Erik’s father, N’Jobu, spurred Erik on a path to avenge his father’s death. Many Black Panther analyses have rightfully pointed out that Killmonger acts as a foil for the African-American identity. He grew up in inner city Oakland, was exposed to structural violence in his community, and over the years developed a dream to liberate black people all over the world.

Was Killmonger a villain? A fallen angel? The absolute worst or the best thing since the Instagram DM? Is Killmonger Problematic Bae? Bae with a Plan? Or Bae for a Night? We saw how quickly he off-ed his literal ride and die, so don’t think any one should be DMing Killmonger, but I get it. The thirst is real in these Wakandan streets.

When it's totally unnecessary to remove your shirt, but the director wants to bless the thirst bucket audience with abs, chest, biceps, and chickenpox.

Instead of critiquing his strategy, I am more interested in dissecting Killmonger’s relationship to home and by extension Wakanda.

The scene that humanized Killmonger was the conversation he had with his father after drinking the purple drank ie: juice of the heart shaped herb. This is actually my favorite scene in the movie. The conversation between Erik and his father was honest and touching. It invites us to explore a key question:

“What is the relationship between Africans on the continent and people of African descent in the Diaspora?”

N’Jobu tells Erik he can not return to Wakanda because they will say he’s “lost.”

Here, lost does not mean physical displacement. Instead, lost is meant in the metaphysical sense. Lost due to the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow that over the years eroded the original cultures of the enslaved. Time and distance meant that over time the two groups diverged in culture, customs, and habits. The spirit of Africa flows in the Afro-peoples of the New World, and these connections are fascinating. Yet to some people on the continent, the lack of direct connection to a compound, to one’s roots begets an image of homeless identity.

N’Jobu was right when he said Wakandans would say Erik was lost. And he says this line with sorrow, knowing full well that his homeland, Wakanda, would never be his son’s. This is a level of rejection young Erik does not comprehend yet. I think Ryan Coogler made a deliberate choice to have the scene played by young Killmonger as to highlight the injustice in telling a child he has no ties and is lost. It also highlights that Erik will forever continue being lost in the world, as a child, teenager, young adult, and grown man.

Herein lies the genius of this film and movie. Erik does not stay lost. Erik grows up, and now the ancestral plane scene cuts to the older Erik, now Killmonger who tells his dad “maybe Wakanda is lost, and that’s why they can’t find us.”

Y’all. This was screenwriting vibranium.

This whole time, we are made to believe that Wakanda's concealment was in self-defense. And while we may agree that Wakanda could have done more to help oppressed people, their choice to don an invisibility cloak was supposedly well intentioned.

Killmonger flips the entire script. He is not lost, Wakanda is.

Wakanda is lost for turning its back on black people all over the world. Wakandans, with all their rich history, pride, and excellence that they wear on their chest, are in fact lost in paradise. A flourishing and privileged society with no sense of where to go. In this moment, I most agreed with Killmonger’s character.

Wakanda can serve as a metaphor for successful black people who hide themselves from their community and the plight of their skinfolk. I am looking at you, Ben Carson, Stacey Dash, and Omorosa. With all the influence these characters have amassed by strategically aligning themselves to white power structures, they have become lost in process, presumably drinking Mai-Tais with supremacy cherries in the sunken place.

Yes We Can! not.

Dashing through this supremacy., with a one way open betray.

When tokens are meant to be seen, not heard. "Shh Shh, Omie"

Make no mistake, I do not think Wakandans are Ben Carson or Omorosa (I could go to Wakandan jail for such blacksphemy). But somewhere in their desire to protect their way of life and not be found, Wakandans became lost.

They never developed the Pan-African sentiment that propelled a significant portion of the black liberation movement in the 19th and 20th centuries. T’Challa even mentions not wanting to fight for people who are not their own. Wakanda, the lost country, have no brethren. How could they find what they don’t know exists? And due to their self-imposed isolation, black people around the globe were left behind, including young Erik, who is literally left behind by a Wakandan king.

Wakanda doesn’t stay lost, of course. Killmonger finds his homeland. After years of training, he finally arrives at his paternal home (Hey, Aunty!) But unlike the ancestral plane experience of T’Challa, who is transported to an ethereal Savannah in Wakanda, Killmonger is transported to his home in Oakland.

This conscious choice by Coogler further highlights the disconnect between Killmonger and Wakanda. And with the beautiful conversation that arises afterwards, Coogler is inviting us to reflect on the distinction between Africans and the Diaspora, between home and homeland, and what happens when the two are in sync, as with T’Challa, or when they are at odds, as with Erik aka Killmonger aka N’Jadaka.

Furthermore, the fact that Killmonger is the only character with multiple names emphasizes the disjointed nature of his identity arising from the conflict between home and homeland. Erik, the young black kid with potential from Oakland; Killmonger, the CIA operative and agent of imperialist America; N’Jadaka, member of the Wakandan royal family.

Killmonger is a beautifully tragic character. After spending his whole life trying to find Wakanda, after finally seeing the Wakandan sunset, he is presented with the option to remain in Wakanda. Killmonger declines and utters one of the movie’s most powerful lines:

“Nah, just bury me in the ocean with my ancestors that jumped from the ships. Because they knew death was better than bondage.”

Killmonger had finally reached his homeland, but he would never call Wakanda his home. Despite his dream of liberating black people around the globe, in Wakanda, a country where BlackExcellence flows from waterfalls, he himself would never be free.

"The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth" (and look really good doing it too).

Part 4: Vibranium Is Where Home Is

Vibranium is the source of Wakanda’s power. It fuels their weapons, strengthens their clothes, and heals their sick. Vibranium is also only found in Wakanda, and with that precious metal, Wakandans built a nation they can proudly call home.

When I returned to my mom’s compound in Etiti, I too discovered a precious and powerful resource in that community. That is the support and unconditional love of my relatives. The sort of love that feels evolutionary in nature, inscribed into our shared DNA, distributed by our shared blood. This love was my own kind of vibranium. Had I lived in that community my whole life, that love would have fueled me and affirmed me in ways I cannot even imagine.

If we think about our lives, our communities, our homes, and our homelands, we could come up with the “vibranium” these locations possess that empower us, inspire us, heal us, and make us feel whole. These sources of vibranium are to be cherished and shared.

This is why I remembered Christmas Day, 2011 in my mom’s village after seeing the movie. Wakanda reminded me of my own ancestral home in Imo State, Nigeria. A home I have been to less than 5 times in my life, but is integrally woven into the tapestry of my life. It’s a home where the vibranium of unconditional love resides.

Simple line. Powerful sentiment.

Black Panther is a movie about a lot of things. It is a love letter to black people, a meditation on methods of liberation, a testament to strong women, a celebration of afro-futurism. We see fashion, slayage, tradition, and modernity. We see ourselves.

Amidst these themes, Black Panther is at its core a movie about our roots. Our compounds. Our homes. And the importance of cherishing them. Why?

Because Home is Where the Vibranium Is.

-Wahala Jr.

Me circa 1995 digging for vibranium in my paternal village, Isiekenesi, Imo State, Nigeria.